How browsers work and render pages

Front-end technologies are sky rocketing in popularity in the last few years. The holy trinity of Front-End - HTML, CSS and JavaScript, are used across different devices and environments - from games, through desktop applications, to robotics. But when we talk about front-end development, one thing always comes to mind first and that is web browsers.

All of us use browsers, but few know how they actually work. We are so used to them, that we take them for granted, but behind every browser lie millions of lines of code. In the next few paragraphs, I will try to show you how exactly browsers work.

How browsers work

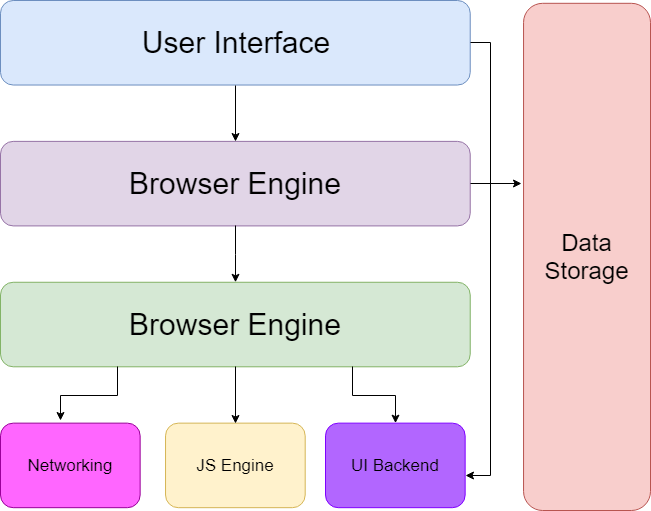

At a high-level, all web browsers are composed of 7 parts:

- The user interface - it’s the space where the user interacts with the browsers. This includes the address bar, back and next buttons, home button, refresh, bookmarks, etc. Every part of the browsers, except the window where you see the requested page.

- The browser engine - the browser engine works as a bridge between the User Interface and the rendering engine and communicates with the Data Storage Component.

- The rendering engine - responsible for displaying requested content. For example, if the requested content is HTML, the rendering engine parses the HTML and CSS and displays the parsed content on the screen. With the help of plugins, the rendering engine can also display other media like PDF documents.

- Networking - responsible for handling network tasks such as HTTP requests, Web Sockets, Web RTC (Uses Real-Time Transport Protocol, which uses UDP). The network component may also implement a cache of retrieved documents in order to reduce network traffic.

- UI Backend - used for drawing basic widgets like combo boxes and windows. This backend exposes a generic interface that is not platform specific. It underneath uses operating system user interface methods.

- JavaScript Interpreter - used to parse and execute JavaScript code.

- Data storage - this is a persistence layer. Used for HTTP Cookies, Browser caching, Web APIs, such as Web Storage and IndexedDB.

The Rendering Engine

The responsibility of the rendering engine is to display the requested contents on the browser screen. By default the rendering engine can display HTML and XML documents and images. It can display other types of data via plug-ins or extensions, for example displaying PDF documents.

Different browsers use different rendering engines: Internet Explorer uses Trident, Firefox uses Gecko, Safari uses WebKit, Opera and Chrome uses Blink, which is a fork of WebKit.

Main flow of Rendering

The main flow is always the same - the rendering engine start getting content of the requested document from the networking layer. After that this is the basic flow of the rendering engine:

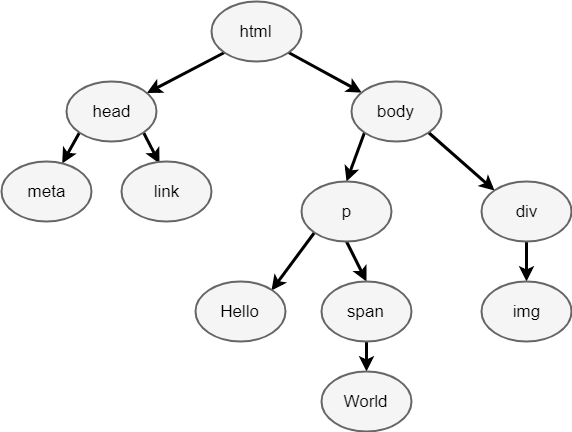

First, the rendering engine will start parsing the HTML document and convert elements to DOM nodes in a tree called ‘content tree’, which looks like that:

The final output of this entire process is the Document Object Model (DOM) of our simple page, which the browser uses for all further processing of the page. Every time the browser processes HTML, it goes through the same steps:

- Convert bytes to characters - the browser reads the raw bytes of HTML and translates them to individual characters.

- Identify tokens - converts strings of characters into distinct tokens, for example -

<html>,<body>, etc. - Convert tokens to nodes - tokens are converted into objects, which define their properties and rules.

- Build the DOM tree - finally, the created objects are linked in a tree data structure that captures the parent-child relationships defined in the original markup.

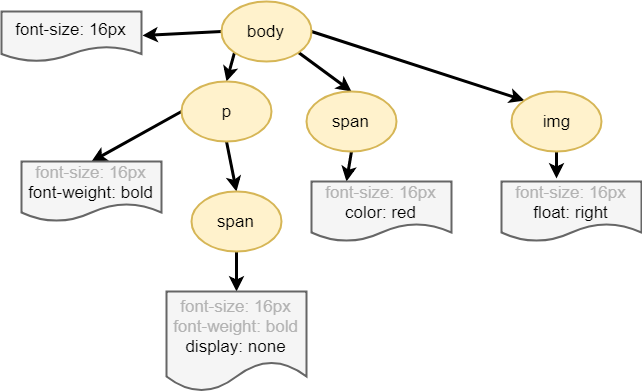

While the browser was constructing the DOM, it may encounter a link tag in the head section of the document, referencing an external CSS stylesheet. The browser immediately dispatches a request for this resource, which comes back with, lets say, the following content:

body { font-size: 16px }

p { font-weight: bold }

span { color: red }

p span { display: none }

img { float: right }

As with HTML, we need to convert the received CSS rules into something that the browser can understand and work with, so the browser repeats the same process - Bytes -> Characters -> Tokens -> Nodes -> CSSOM

Why does the CSSOM have a tree structure? When computing the final set of styles for any object on the page, the browser starts with the most general rules applicable to that node and then recursively refines the computed styles by applying more specific rules; that is, the rules ‘cascade down’.

Note that the above tree is not the complete CSSOM tree and only shows the styles we decided to override. Every browser provides a default set of styles also known as ‘user agent styles’.

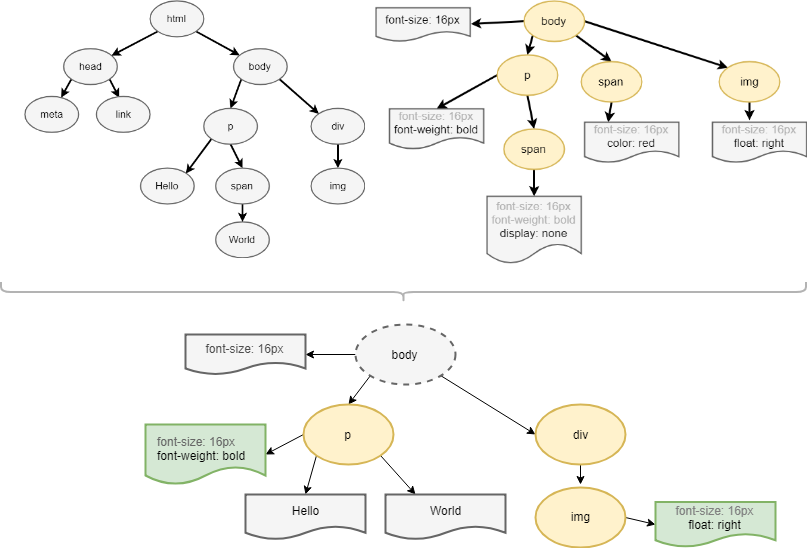

After the rendering engine creates the DOM and CSSOM, it combines them into a render tree, which is used to compute the layout of each visible element and serves as an input to the paint process that renders the pixels to the screen. If the style is not loaded and parsed yet, the script will get wrong answers and apparently this can cause lots of problems. It seems to be an edge case but is quite common. Browsers implement different strategies for these scenarios; for example, WebKit blocks scripts only when they try to access certain style properties that may be affected by unloaded style sheets.

To construct the render tree, the browser does the following:

- Starting at the root of the DOM tree, traverse each visible node.

- Omit nodes that are not visible (script tags, meta tags, and so on). They do not reflect the rendered output.

- The hidden via CSS nodes are also omitted from the render tree: for example the span node - in the example above, because of the “display: none” rule.

- For each visible node, find the appropriate matching CSSOM rules and apply them.

- Emit the visible nodes with content and their computed styles.

The final output is a render that contains the content and style information of all the visible content on the screen. We can now proceed to the layout stage.

When the render tree is created, for each element, its coordinates are calculated. The layout is a recursive process. It begins at the root renderer, which corresponds to the <html> element of the HTML document. Layout continues recursively through some or all of the hierarchy, computing geometric information for each renderer that requires it.

The position of the root is 0,0 and its dimensions are the viewport- the visible part of the browser window

Finally, now that we know which nodes are visible and their computed styles and geometry, we can pass this information to the final stage, which converts each node in the render three to actual pixels on the screen. This step is often referred to ‘painting’ or ‘rasterizing’:

The order of processing scripts and style sheets

The model of the web is synchronous. Developers expect scripts to be parsed executed immediately when teh parser reaches a <script> tag. The parsing of the document halts until the script has been executed. If the script is external then the resource must first be fetched from the network–this is also done synchronously, and parsing halts until the resource is fetched. Developers can add the defer attribute to the script, in which case it will not halt document parsing and will execute after the document is parsed.

While scripts are executed, another thread can parse the rest of the document and finds out what other resources need to be loaded from the network and loads them. This is called speculative parsing. In this way, resources can be loaded in parallel connections and overall speed is improved. The speculative parser only parses references to external resources like scripts, styles sheets and images.

Style sheets have a different models. Conceptually it seems that since style sheets don’t change the DOM tree, there is no reason to wait for them and stop the document parsing. There is an issue though, of scripts asking for style information during document parsing stage.

What is “reflow” and what causes it

Reflow happens when the browser must re-calculate the positions and geometries of elements in the document, for the purpose of re-rendering part or all of the document. The reflow is a user-blocking operation in the browser, so it’s useful for developers to understand how to improve reflow time. There is a great document, outlining which properties forces reflow - What forces layout / reflow.

There are several guidelines to help you minimize reflow:

- Reduce unnecessary DOM depth.

- Minimize CSS rules and remove unused CSS rules

- Avoid unnecessary complex CSS selectors - descendant selectors for example - which require more CPU power to do selector matching.

- If you make complex rendering changes such as animations, do so out of the flow.